It was the most dispiriting of anniversaries for Shakhtar Donetsk last month. Their exile is now into its second decade. The Donbas Arena, one of Europe’s great new arenas when it was opened ahead of Euro 2012, lies abandoned, still scarred by shelling when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014.

Their home city now occupied by Russian troops, the Yellow Ribbon movement have left their mark on the Donbas Arena. In April, Ukrainian media reported that the road to the stadium had been pockmarked with yellow ribbons, a sign of continued resistance in a conflict that seems no closer to ending.

The mere act of playing football in wartime brings with it scarcely imaginable logistical challenges for Shakhtar, from arduous travel to their frustrations with FIFA. This club that was forced from its home at a time of division across Ukraine — which in 2014 was divided by pro- and anti-Russian protests, the former fanned by Vladimir Putin and his “little green men” — aspires to be a beacon for the nation.

Please check the opt-in box to acknowledge that you would like to subscribe.

Thanks for signing up!

Keep an eye on your inbox.

Sorry!

There was an error processing your subscription.

Shakhtar forced to leave Donetsk in 2014

“Our story starts in 2014 with the first wave of invasions,” chief executive Serhii Palkin tells CBS Sports. “We left our stadium, we said goodbye to our fans and lost our beautiful stadium, at that moment one of the best in Europe. We moved to Kyiv to stay and train, but played in Lviv. At that moment, we wanted to unite the whole country. There were contradictions between the east and west, we wanted to show that we were united. We wanted to be for one country. Moving to the west was very, very important.

“For 10 years, we are out of our home. We are quite a unique club in this situation. Look at world football history, you will never find examples like our club. At the same time, we’ve managed to maintain the sporting levels of our club. To develop even.”

For a time, they were just about able to develop. From Lviv to Kyiv via Kharkhiv, Shakhtar continued with the blueprint that had made them one of Europe’s most admired talent factories. Alex Teixeira, Fred and Tete were among the Brazilians whose journey to acclaim took them through the club. Manchester City, Real Madrid and Napoli were among the big names defeated on the continent by a side who never finished lower than second in the domestic league. Until Russia advanced further east in 2022, Shakhtar were making it work.

Total war makes Shakhtar more than a club

Then the full-scale invasion happened. In the space of a fortnight, the club had to evacuate its international players from Ukraine — before long it would find that the financial value they represented would be obliterated — and pivot from football club to social institution. As shown in CBS Sports’ Emmy award-winning docuseries “Football Must Go On,” Shakhtar truly became more than a club. They were a shelter for refugees from the east, organizers of medical support, food and psychological aid. Amputee soldiers could don the Shakhtar kit and form a team. Before too long, the Miners were among those Ukrainian clubs whose tour of Europe raised a seven-figure sum for those who needed it back home.

Football resumed, a necessary message to send to those in Ukraine, Russia and beyond, as Palkin puts it. Do not for a moment, however, assume that Shakhtar were even back to the circumstances that they found themselves in after 2014. Not when the mere act of completing one football match can be a labor of physical and emotional endurance.

Take, for instance, their match away to Dnipro-1 on the penultimate weekend of last season. Marino Pusic’s side might already have secured the league title but for their hosts the stakes were sky high. Dnipro-1 were battling for qualification for the Conference League and European football, Palkin notes, is a vital source of revenue in a league without spectators in many games.

The first half brought with it the two goals of this vital game. It also necessitated two pauses in play, not from the referee’s whistle, but from the air raid siren. Nineteen minutes of play and the match is disrupted by the warning siren. Another seven minutes and the players must exit the field. It would be over an hour before they were back on the pitch. It would be much longer with more sirens to come before the referee blew the final whistle.

“It lasted six hours,” says Palkin. “Can you imagine? We started playing and again the alarm. And again. Six hours, from a psychological and physical point of view, it’s very, very difficult to play.”

Shakhtar persevere as the war persists

Those are the more trying moments, but Palkin is at pains to reflect on the monotony too. Players live in hotels without their families, many of whom have left Ukraine for the greater safety of Europe. The squad’s routine, as their chief executive puts it, is hotel, train, hotel. “A difficult life to live.”

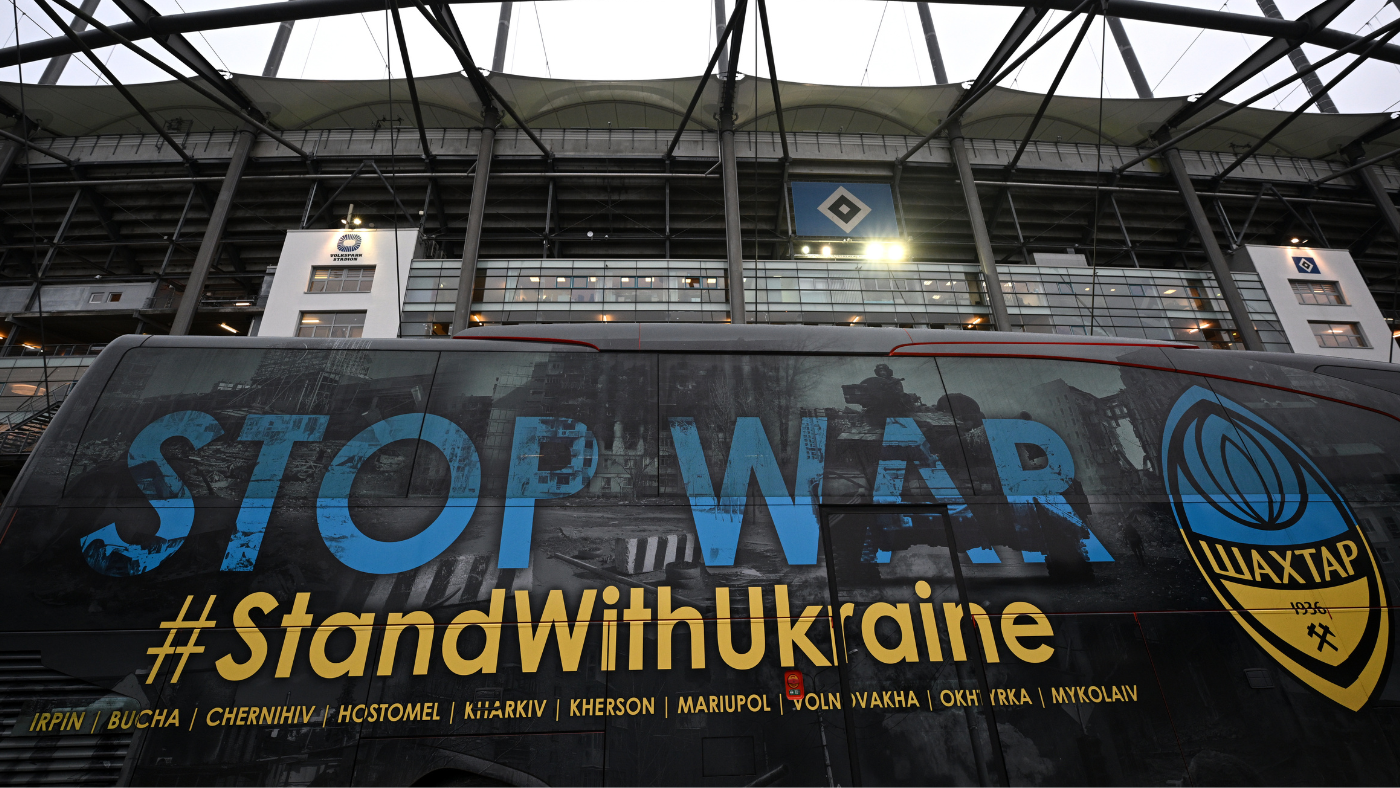

For Ukrainian clubs, even completing their games ought to be viewed as a triumph. The complications only grow for their European fixtures, all of which are played outside Ukraine with Hamburg hosting them last season in the Champions and Europa League. For most Ukrainian men of their age, leaving the country is outlawed. Shakhtar players get an exception for these games. But still, merely getting from the continent’s eastern limits to the far west for a must-win group stage game at Porto was a test of endurance.

“From Kyiv, it took us two days to reach our destination,” Palkin adds. “A day and a half in the bus and then four hours on the plane. Then you arrive in Porto, knowing your opponent is much stronger than you. You’ve lost your physical conditions. It’s almost impossible to be ready for that game.” Despite those trying circumstances, Shakhtar gave Porto an almighty game, twice trimming their hosts’ lead in a winner-takes-all battle for knockout stage qualification before their energy deserted them in the final stages of a 5-3 defeat.

“I was so proud of our young players. I still am.” It is a feeling Shakhtar hope that the rest of Ukraine can share. Their hearts may lie in Donetsk, but over a decade on the road has given Palkin and those he work with a sense of mission to raise the spirits of a nation. “We need to give some positive emotions,” he says. There could be few greater morale boosts that a football team could offer than beating Barcelona, as Shakhtar did in November last year. Even the way in which Palkin frames that night — “when we beat Barcelona for our country” — speaks to his belief in the power of football to shine a light through the darkness.

“There were unbelievably positive emotions that we sent to all people. It showed that even in these very hard times, Ukrainian people can show strength. We want to give hope to our Ukrainian people, to show that we are as strong as ever.”

Playing football in a war zone, traveling to Hamburg for “home” European games, aiding the war effort: None of this comes cheap. The €3 million win bonuses in the Champions League help a pared back Shakhtar squad, but the sale of Mykhailo Mudryk for what ultimately could be €100 million was a necessity, particularly in light of FIFA’s controversial Annex 7. This gave players and coaches in both Ukraine and Russia the right to unilaterally suspend their contract, initially until July 2022, but ultimately through to 2024. Shakhtar and eight Russian clubs challenged FIFA at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) but without success. The likes of Roberto De Zerbi, Manor Salomon and Tete departed without a fee.

FIFA offer ‘zero’ support

“When the war started, foreign players left and FIFA didn’t support us,” says Palkin. “They left us alone and at the same time they pushed us to return and pay back all debts.

“Normally, when you run transfer business, you’re buying players with payments two, three or four years down the road. When the war started we had €40 million of debts. When I have arguments with people asking how it’s possible I can’t sell players or put them on loans, you just make them free and you push us to pay all our debts otherwise you’ll withdraw our football license. Then we cannot participate in European competitions. It was unbelievable.

“From FIFA, from the beginning, we’ve had no support. Zero. When the war started, we tried to contact FIFA to find solutions, to sit at the table and think about the future. FIFA’s door was always closed.

“They did very badly for Ukrainian football and Ukrainian clubs. But FIFA is an untouchable body. Nobody knows how to influence them. They do what they want.

“FIFA always tries to say we are one football family. When the war started, those principles didn’t apply. Nobody even contacted the Ukrainian football league or clubs to see how they could help. This is for me the worst scenario I could ever imagine.”

CAS ultimately sided with world football’s governing body and sources at FIFA insist that they believe they did all they can to find any sort of solution to a conflict that had abruptly escalated in February 2022. While Shakhtar were unhappy with the support they received from FIFA, sources at the organization say that it engaged with as many organizations as possible before introducing Annex 7. It should also be noted that other stakeholders, including player union FIFPRO, had argued that players should be allowed to unilaterally terminate their contracts. Given that no one could know how long the conflict in Ukraine might rage on for, FIFA believes that its solution was the best available at a moment when there were no easy options.

Negotiating the transfer market to stay afloat

Meanwhile, Shakhtar’s frustration about lost revenue has not eased. Mudryk won’t be the last big name to leave. Palkin is expecting “lots of offers” after Euro 2024 for the 21-year-old playmaker Heorhii Sudakov, who, like the club he plays for, was driven from his hometown 10 years ago by the Russian-backed separatists. Napoli had an offer rejected for the player in January and his progress has been closely monitored by the likes of Arsenal, Chelsea, Tottenham and Newcastle. He will “definitely move to a top club in Europe.” That will help the club’s financial situation.

So, Palkin would argue, would be getting some return from those who left following FIFA’s decision. Solomon initially joined Fulham on loan in July 2022. Twelve months later, he signed for Tottenham as a free agent, Annex 7 allowing him to suspend his contract. The two sides played a friendly in London in August, after which a donation was made to the Shakhtar foundation, but Palkin says talks over further remuneration for his club have been on hold for several months.

“Their behavior was very strange,” he added. “When we’re talking about one football family that we should support and help each other, Tottenham didn’t behave like one football family. They received free of charge a player who is worth €25 million on the transfer market. Our club brought this value to the player. We invested in him, we developed him. They just used our club and received a free player.

“When I started negotiations with Tottenham I didn’t ask for money now. I said ‘let’s be partners in this situation. If you will sell Salomon in the future, give us 30 to 35 percent of the fee.’ That would be enough. We would have mutual collaboration. They refused to share even that future profit with us. For me it’s wrong that those kinds of clubs with that kind of level behave like this.”

Tottenham declined to comment when approached by CBS Sports.

The transfer window’s impact on Shakhtar’s future could pale into insignificance compared to events in Switzerland later this week, where Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky hopes to secure further international backing for his 10-point peace plan. U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan are due to attend. Joe Biden is not.

“We cannot stop the war alone,” says Palkin. “We need global support. The most influential leaders should participate, otherwise it will be difficult to stop Russia. Everyone knows why we have to do that, what we’re fighting for.

“Using every tool we can, we’re trying to bring closer peace in Ukraine. We’re doing what we can do in this case.”

Should that peace come, Shakhtar might finally be able to go home. Most of their squad have never played at the Donbas Arena. If they do so again it will have been after a pan-Ukraine odyssey longer than The Odyssey. Still hope lingers.

“Our DNA is in Donetsk. All our management, the president of our club, we are all from the city. We always talk of Donetsk. We’re always dreaming of going home.”